She wins medals. She breaks records. She lifts a nation’s pride. And yet, she barely earns the headlines—or the money.

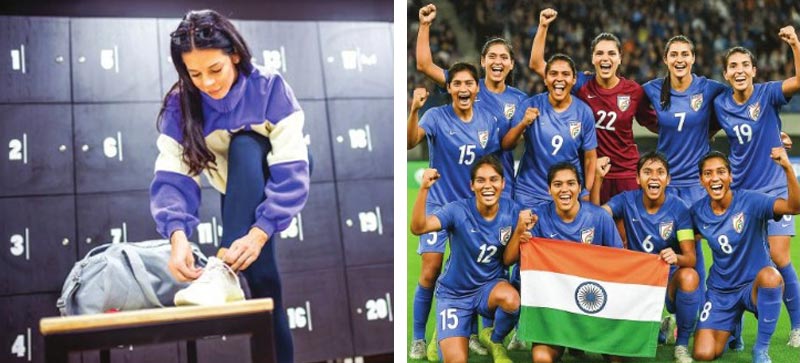

For the first time in the history of sports, the Indian Women’s National Football Team—affectionately known as the Blue Tigresses—have qualified for the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) Women’s Asian Cup 2026, marking a momentous first-time qualification via merit (not as hosts). Sangita Basfore, the midfielder in the Indian Women’s Football Team led India to a historic AFC Asian Cup 2026 qualification. But unless you follow obscure hashtags, you probably missed it.

What should have been hailed as a tipping point in Indian sports history is barely known. For the first time, India’s women’s football team has a real shot at the global stage—aiming to finish among the top six in Asia to secure a place in the FIFA Women’s World Cup qualifiers or playoff contention. The AFC Women’s Asian Cup 2026, set to be held in Australia from March 1–21, 2026, doubles as a gateway to the 2027 FIFA Women’s World Cup and the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics. In short, this is not just another tournament—it’s India’s golden ticket to elite international football.

India’s sports women have carried the nation on their shoulders in global arenas—from Mary Kom’s punches to PV Sindhu’s smashes, from Mirabai Chanu’s Olympic lifts to the Blue Tigresses’ historic AFC Asian Cup qualification. But even as they bring home the glory, the spotlight continues to shine mostly on their male counterparts—win or lose.

How many of us even know that Annu Rani, India’s javelin queen, is a national record holder who has been quietly rewriting the women’s circuit while all the spotlight falls on Neeraj Chopra? Or that Savita Punia, the goalkeeper of India’s women’s hockey team—nicknamed the Wall of India—was instrumental in our Olympic semi-final run in Tokyo? And then there’s Manasi Joshi, a para badminton world champion and techie-turned-athlete, who is a fierce voice for inclusivity in sports—yet is overshadowed by more famous names.

So why are Indian Sports-women not celebrated like the men. Despite consistent medal wins, record-breaking feats, and international glory, Indian sportswomen often remain footnotes, not front-page headlines. Why does India still celebrate its sportsmen but sideline its sportswomen?

In Shabaash Mithu, one of the most gut-punching scenes unfolds at the airport: the Indian women’s cricket team returns after a valiant World Cup run—bruised, battered, yet proud. But there’s no media frenzy, no garlands, no applause. Just silence. Moments later, the men’s team arrives—having lost their match—and the same airport erupts in cheers, flashbulbs, and flower showers.

The contrast is jarring. The women, who’ve achieved history, are ghosted. The men, who’ve faced defeat, are still feted. It’s not just a scene—it’s a mirror to society’s deep-rooted bias. That single frame says everything about the gender gap in sports: talent doesn’t always bring recognition. Sometimes, it’s just the jersey you wear.

The film scene spotlights how society often values male failure over female success.

And this is not the movie scene. It resonates with reality.

The corporate sponsorship is Male-Heavy. According to a KPMG report, over 85% of sports marketing budgets in India go to men’s cricket. Women athletes struggle to get endorsements—even Olympic medallists like Lovlina Borgohain or Mirabai Chanu aren’t brand ambassadors for major national campaigns the way cricketers are.

“I had to win an Olympic silver to be noticed. A male cricketer gets 100x visibility without winning anything,” said a female Olympic medallist privately.

Yes even corporate India is complicit in this bias. While male cricketers sign multicrore brand endorsements, women athletes—even Olympic medallists—struggle to land a single major campaign. PV Sindhu, India’s most marketable female athlete, still earns less than a benchwarmer in IPL. That’s not just unfair—it’s irrational. “Brands want ‘reach’, not reality,” says a former sports agent. They still believe men sell better. That belief needs an audit.

Plus the cricket monopoly drowns all else. Cricket is a religion, yes—but only for men. The Women’s Premier League (WPL) was a breakthrough, but still gets a fraction of the airtime and budget of the men’s IPL.

Our social conditioning still screams: “Sport is not for girls.” In countless Indian homes, daughters are told to “sit properly,” not run too much, and stay away from “rough games.” Boys get bats; girls get dolls.

“My brother played district matches,” recalls a young sprinter from Haryana, “I had to fight just to get shoes.” The bias runs so deep that in the recent tennis player Radhika’s case, her father faced social humiliation—not because she failed, but because her success was deemed unacceptable. From facilities and access to safety and late training hours, everything is skewed in favour of boys.

At its core, Indian sport is still trapped in a masculinity myth—where strength, aggression, and competitiveness are considered male-only traits. So when a woman dares to be both feminine and fierce, society struggles to reconcile it. The result? Absurdities like Sania Mirza’s attire making bigger headlines than her backhand, or Mithali Raj, fresh off a match-winning century, being asked about her “favorite male cricketer.”

A senior sports editor admitted:

“We’re pushed harder to cover IPL afterparties than a world championship won by a female wrestler.”

When the men’s cricket team sneezes, it’s breaking news. But when the Indian women’s football team qualifies—on merit—for the AFC Asian Cup 2026, it’s reduced to a fleeting ticker.

“We’re not asking for fame. Just fairness,” says Harmanpreet Kaur, Captain of the Indian Women’s Cricket Team.

However, change is coming—slowly, but surely. Social media is now the parallel arena where female athletes tell their stories, bypassing the filters of legacy media. Take the case of Yuwa, the grass- roots revolution from rural Jharkhand, founded by US-based Franz Gastler. What started with one girl’s request to learn football has grown into eastern India’s largest girls’ football movement. Yuwa is more than a sports program—it’s a fight against child marriage, illiteracy, and trafficking, while nurturing education, confidence, and leadership in young girls. Today, over 250 girls play regularly—150+ every single day—on village teams, most coached by women who once wore the jersey themselves.

The Women’s Premier League (WPL), initiatives like Khelo India, and increasing medal visibility have helped. Today, PV Sindhu, Mary Kom, Saina Nehwal, Hima Das, Dipa Karmakar, Rani Rampal, and Mithali Raj are finally becoming household names.

But true change will come only when we celebrate consistency—not just the medal moments. When women’s sport stops being treated as charity content and becomes truly prime-time worthy.